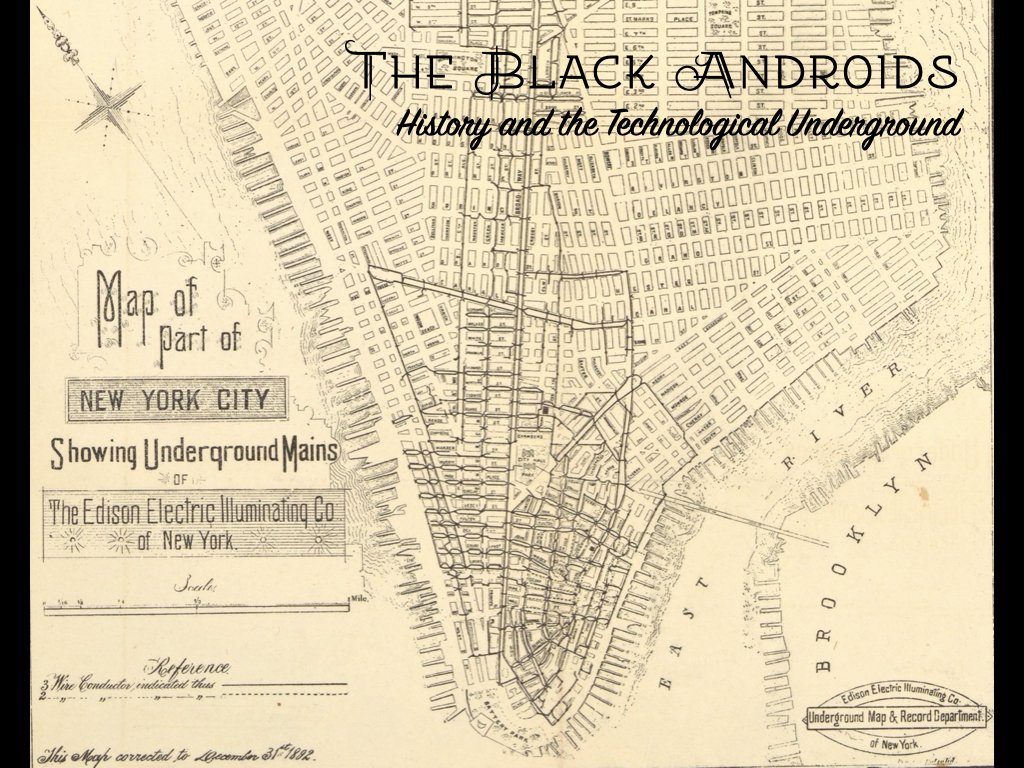

The Black Androids: History and the Technological Underground

History of Science Colloquium

History of Science Colloquium

Panel Discussion

Monday Night Seminar

Colloquium

Society for the History of Technology Annual Meeting

The aim of this workshop is twofold: The first part highlights the topical issue of technological selfhood, that is to say the reciprocity of “how we make machines and machines remake us” (Peter Galison). The second part of the workshop is devoted to new perspectives on science and technology during the Cold War. How did this conflict operate as an “intellectual force field” (Nils Gilman) that helped shape knowledge production, technology, and (self-)perception? Both questions can be tackled separately, but also intertwined. The workshop is based on the research interests of our invited guest, Edward Jones-Imhotep. He is currently working on a new book project on reliable humans and trustworthy machines, from the guil- lotine in revolutionary France to industrial breakdowns in the American Jazz Age.

Edward Jones-Imhotep is Associate Professor of History at York University, Toronto. He received his PhD in the history of science from Harvard University. He is the author of The Unreliable Nation: Hostile Nature and Technological Failure in the Cold War (MIT Press, 2017) and the award-winning essay “Mallea- bility and Machines: Glenn Gould and the Technological Self” (2016 winner of SHOT’s Abbot Payson Usher Prize).

This lecture explores the natural history of cold-war technologies. The machines of the Cold War were developed in dialogue with conceptions of “hostile” nature — punishing natural environments, turbulent natural phenomena, violent natural effects. Knowing these hostile natures, however, required new practices for representing them and for imagining their relationship to the machines of the Cold War. This talk focuses on the attempts of Canadian cold-war scientists to make “sporadic" atmospheric phenomena knowable, and to transform these potentially hostile effects into elements of a stable infrastructure for Cold War communications. Tracking those efforts through scientific images, experimental satellites, clandestine maps, and machine architectures, the talk argues that the history of survivable communications during the Cold War is, in part, a natural history: a history of the hostile and turbulent natural orders that developed in conversation with fallible machines.

The roundtable will begin with three 15-minute talks. The first by Hans Peter Brondmo, a Norwegian native who leads one of Google X’s robotics projects. X describes itself as a ‘“factory...with the mission to invent and launch “moonshot” technologies that we hope could, someday, make the world a radically better place’. The second talk will be given by Edward Jones-Imhotep, Associate Professor, History of Technology at York University, Toronto, where he focuses on the intertwined cultural histories of reliable humans and trustworthy machines. The third will be given by Prof. Eric Bartelsman, General Director at the Vrije Universiteit and Tinbergen Institute where he is an economist focusing on productivity growth.

This talk explores how the global history of the Cold War played out through two semi-secretive technological projects of the period. The first was the attempt, during the 1950s and 1960s, to overcome massive communications failures in the Canadian North – naturally-occurring radio blackouts that would mask incoming ICBMs and disrupt shortwave technologies. The talk traces how these failures helped define the “hostile natures” of the Cold War, as well as Canada’s cultural anxieties and geo-political vulnerabilities during the period. The talk’s second focus is the late 1960s, where it traces the “supergun” projects of Gerald Bull, the former McGill professor turned international arms dealer. Bull’s ambiguous inventions – gargantuan cannons initially designed to launch probes into space – straddled the line between scientific instruments and illicit weaponry. Conceived in Montreal, deployed in Barbados, redesigned and sold to South Africa, and eventually enlarged and destined for Saddam Hussein’s Project Babylon, they would ultimately lead to Bull’s assassination at the hands of government agents outside his Brussels apartment. Contrasting the two episodes, the talk illustrates the crucial historical and geographical connections between Canadian science and technology and the broader, global contours of the Cold War.

This talk explores how modern observers from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries understood the failure of machines as a problem of the self— a problem of the kinds of people that failing machines created, or threatened, or presupposed. The modern period saw the rise of a public theatre of machines, whose failure threatened the social relations, political priorities, and economic interests that depended on it. For all the large-scale disruptions that failing machines occasioned, though, contemporaries framed their most pressing worries around small-scale concerns about the self, and specifically about what kinds of people we are (or should be) in the face of failing machines. From 18th-century sentimentalism and the guillotine, through Victorians’ nervous fascination with railway accidents, to industrial breakdowns in Jazz-Age America, this talk excavates the largely-forgotten sources, settings, characters, and concerns that linked selves and social orders to the problematic workings of technology. Connecting those developments to our own worries in the early 21st century, the talk encourages us to reimagine the history of modern technology as a history of the technological self, and the machines and social orders it made possible.

This talk is the tenth session in the UBC History Department's Colloquium Series 2017 - 2018: Histories on the Edge. It is co-sponsored by the UBC STS Program.